$166k worth of telecom fraud hits small firm

This small architectural firm got hit with a telecom fraud attack. $166,000 losses. In one weekend. Don’t let this be you.

The $166,000 telecom fraud story

Plain old telephone service (POTS) is a potential $100,000+ liability bomb that could explode at any time. Just ask Bob Foreman, of Foreman Seeley Fountain (FSF), a seven-person architectural firm of Norcross, Georgia.

Bob Foreman, architect

FSF had four analog telephone lines provided by TW Telecom, and now they are facing a bill for $166,000 in telephone charges that could bankrupt their business.

Jeff Seeley, Vice President of FSF, describes their experience. “We have been in business since 1985. We survived the great recession when many of our colleagues in the building industry lost their jobs or went bankrupt. We struggled through all of that and now we are about to be put out of business by a telephone company”, Seeley states shaking his head.

How could something as basic as telephone service be a bankrupting financial risk for consumers and small businesses? Based on FSF’s normal monthly telephone bill, it would take over thirty-four years to use $166,000 worth of telephone service. What has gone wrong? The answer is simple. Telecom traffic pumping fraud is a rapidly growing trend that is destroying the integrity of the public telephone network.

Telecom traffic pumping fraud occurs when a fraudster uses your phone to send calls to an expensive Premium Rate Number (PRN). Calls to premium rate numbers are similar to superexpensive long distance calls on your phone bill. The telephone company charges the calling party a high rate and then shares the charges with the owner of the premium rate number.

For example, in the USA any telephone number beginning with 1-900 is a premium rate number. The calling party will be charged a premium rate on their phone bill when they call a 1-900 number.

International Premium Rate Numbers (IPRN) usually do not have an obvious prefix, such as 1-900, that identifies them as a premium rate number. Even worse, IPRNs in most Caribbean countries are ten digits and look like US telephone numbers.

The traditional business model for Premium Rate Numbers makes sense when the Premium Rate Number owner is a legitimate business such as a fan club or a charity that uses the calls to collect payments. Unfortunately, fraudsters have learned that Premium Rate Numbers are a very easy way to make money. Dozens of Premium Rate Number owners eagerly offer a cash payment to fraudsters who send calls to their Premium Rate Numbers – with no questions asked.

Telecom traffic pumping fraud is growing dramatically, and anyone with a telephone is at risk. If a fraudster hacks your telephone, your telephone service provider will hold you responsible for all fees and may sue to collect.

The really sinister aspect of telecom traffic pumping fraud is that every telephone service provider in the chain of networks that carry a call from the calling party to the premium rate number provider has a legal obligation to pay interconnect fees to the downstream network, even if the calls are obviously fraudulent. In addition, there is a strong financial incentive for every telephone network to aggressively collect the revenue for fraudulent calls.

When traffic pumping fraud occurs, the telecom business model offers no incentive to protect the consumer or small business that was hacked. In fact, it is worse: the telecom business model has structural incentives that maximize the liability for the fraud victim. This is the fact that Foreman Seeley Fountain has learned.

The telecom fraud attack

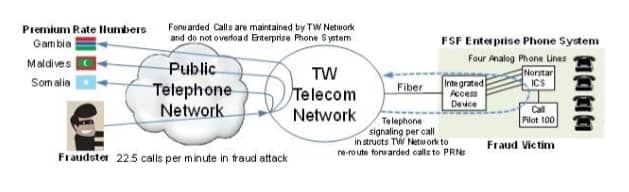

FSF’s phone system is a Norstar Modular ICS and Call Pilot 100 key system served by four analog lines coming from an integrated access device (IAD) connected to TW Telecom’s optical fiber network.

In March of 2014, a fraudster called FSF during non-business hours, hacked the password protection of the Call Pilot 100 auto-attendant and configured call forwarding to premium rate numbers in Gambia, Senegal and the Maldives.

The following call flow diagram illustrates the most likely call scenario for the fraud attack:

Anatomy of a PBX hack telecom fraud attack

- The fraudster probably initiated the attack over the internet using software to generate Voice over Internet Protocol (VoIP) telephone calls to FSF, the fraud victim.

- Those calls were routed from the internet to the Public Telephone Network to TW Telecom that provides telephone service to FSF. When a call reached FSF, the phone system instructed the TW Telecom network to forward the call to a premium rate number (PRN). This signal is the dashed trace looping from TW Telecom to the FSF phone system back to TW Telecom.

- After the call forwarding signal is sent to TW telecom, the FSF phone system is no longer in the call path and is available for another phone call. The forwarded call was completed by TW Telecom to the Premium Rate Number and maintained by the TW Telecom network until the call was disconnected.

During the peak of the attack, there was an average of 22.5 completed calls per minute—one call every 2.67 seconds. Of these calls, 1,590 lasted between one to four hours. This call-forwarding technique enabled the fraudster to generate over 568 simultaneous calls from a phone system with only four analog lines.

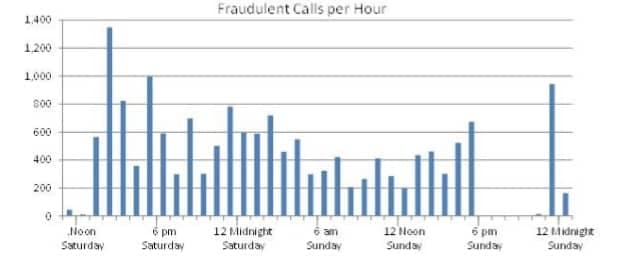

The fraud attack began before noon on a Saturday and was finally detected and blocked by TW Telecom just after midnight early Monday morning. The chart below shows the calls per hour during the fraud attack.

99.6% of all calls in the fraud attack were forwarded to three telephone numbers in Gambia:

| Called number | Calls | Minutes | Minutes/call | Share of calls | Share of minutes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2206501502 | 9,150 | 261,693.1 | 28.6 | 56.6% | 55.9% |

| 2209015142 | 3,514 | 115,297.3 | 32.8 | 21.7% | 24.6% |

| 2206501503 | 3,428 | 90,878.3 | 26.5 | 21.2% | 19.4% |

| 14 other numbers | 69 | 559.6 | 8.1 | 0.4% | 0.1% |

| Totals/averages | 16,161 | 468,428.3 | 29.0 | 100.0% | 100.0% |

Just four calling numbers were used in the fraud attack. Two of the numbers represented 92.9% of all calls. A reverse white pages lookup reveals that the numbers beginning with 678 are assigned to Time Warner Communications, Inc. and the number beginning with 770 is assigned to AT&T. While interesting, this information is not reliable, since the calling number can be easily spoofed using Voice over Internet Protocol (VoIP) tools.

| Calling number | Calls | Minutes | Minutes/call | Share of calls | Share of minutes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6789062071 | 10,117 | 299,937.6 | 29.6 | 62.6% | 64.0% |

| 7707298433 | 4,894 | 128,462.8 | 26.2 | 30.3% | 27.4% |

| 6789062072 | 1,141 | 39,944.1 | 35.0 | 7.1% | 8.5% |

| 6789062070 | 9 | 83.8 | 9.3 | 0.1% | 0.0% |

| Totals/averages | 16,161 | 468,428.3 | 29.0 | 100.0% | 100.0% |

FSF had no idea their phone system had been hacked until they received the bill from TW Telecom with $166,000 in international long distance fees. TW Telecom holds FSF fully responsible for the fees and has threatened to sue if they do not receive full payment.

FSF had two choices: liquidate the company to pay their phone bill, or fight. FSF has decided to fight, and has filed a complaint with the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) against TW Telecom.

FSF understands they have a responsibility to secure their phone system, but they do not believe they should bear 100% of fraud losses.

If FSF were to pay their bill, it would be an extraordinarily profitable event for TW Telecom—wholesale traffic volume priced at retail rates. The FSF complaint to the FCC puts a spotlight on the structural incentives in the telecom industry that encourage traffic pumping fraud and maximize the fraud risk for telecom consumers.

The call flow diagram presented earlier illustrates one irony of this fraud case: not a single fraudulent call originated from within the FSF premises or its phone system. All the fraudulent calls originated from the public telephone network and were delivered to the FSF phone system by TW Telecom.

If FSF had received 22.5 calls per minute during business hours, the attack would have disrupted normal telephone usage for FSF and would have been considered a Telephony Denial of Service (TDoS) attack. If this attack had occurred during the day, the issue for the FCC to consider would be this: should telecom service providers protect their customers from a TDoS attack?

Since this attack occurred during off-hours, the attack went unnoticed by FSF, and the fraudulent calls were successfully completed by TW Telecom. TW Telecom was billed for the calls by the international carrier that completed the international calls. TW Telecom paid its international carrier for the calls even though the calls to Gambia had been identified as fraudulent.

In their complaint to the FCC, FSF argues that, when TW Telecom paid its international carrier for the fraudulent calls, it was in fact aiding and abetting the fraud. TW Telecom had become an active participant in the chain of cash transfers from the fraud victim, FSF, to the international carrier, who paid the Premium Number Service provider, who provided a revenue share with the fraudster.

When FSF subscribed to TW Telecom’s phone service, they had no idea of the financial liability they were accepting. In fact, there is no record that FSF ever requested international telephone service from TW Telecom. In simple terms, FSF believes they were misled, and they decided to fight. FSF has taken their case to the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) with a formal complaint.

Historically, the argument that retail telephone service providers, such as TW Telecom, are complicit with traffic pumping fraud when they demand payment for fraudulent calls has not been successful. In fact, in many ways the retail telephone service provider is also a victim, and it is certainly reasonable to hold the customer accountable for calls from their phone system.

However, the telecom world is changing with the rapid growth in telecom traffic pumping fraud. The practical reality is that telephone service providers must provide their customers some protection from telecom fraud liability.

Consumers and small businesses do not have the expertise to eliminate the risk of telecom fraud. Most consumers and small businesses would refuse to sign a telephone service contract if they understood the risk of traffic pumping fraud and their unlimited liability.

Learn how to prevent telecom fraud attacks faster AND with fewer false positives.

Request the whitepaperThe argument that traffic pumping fraud can only be stopped by interrupting the flow of funds from victims to fraudsters has merit, but is very challenging to implement. Nevertheless, something must be done, the current policy that places all fraud liability on the consumer, regardless of their expertise to control fraud, is not in the public’s interest.

The FCC should consider a public policy that makes fraud control a shared responsibility for both customers and service providers and limits the fraud loss liability for consumers and small business.

Whatever the outcome of FSF’s FCC complaint, we expect that both the FCC and state regulators will place greater responsibility on service providers to protect their customers from traffic pumping fraud and from TDoS attacks.

Progressive telephone service providers have an opportunity to differentiate themselves and build brand loyalty by educating their customers about the critical benefits they provide by protecting their customers from traffic pumping fraud and other telecom attacks.

More on TransNexus.com

February 15, 2023

Suggestions to curb access arbitrage

June 27, 2022

FCC proposes new rules to prevent access stimulation

June 6, 2022

Denial of service attack and ransom demand defeated

May 18, 2022

China cracks down on telecom fraud

December 6, 2021

Telecom fraud losses increasing, according to CFCA report

December 1, 2020

FCC Report and Order on one-ring scam calls

November 9, 2020

Domestic telecom toll fraud is still a problem

October 12, 2020

FCC changes rules for intercarrier compensation on toll free calls

January 23, 2020

TRACED Act calls for one-ring scam protection

November 19, 2019

Robocall and TDoS case studies

October 28, 2019

FCC denies stay request on their Access Arbitrage Order

October 28, 2019

Wangiri telecom fraud activity reported in Canada

September 26, 2019

FCC issues order to prevent access stimulation

July 16, 2019

ClearIP adds new call forwarding blacklist capabilities

July 10, 2019

July holiday week telecom fraud attack profiles

June 13, 2019

ClearIP enhancements for blacklisting of SPID and location

May 20, 2019

Anatomy of a telecom fraud attack

May 14, 2019

Study on rule changes to eliminate access arbitrage

May 8, 2019

FCC warns of Wangiri telecom fraud scams

March 8, 2019

SIP Analytics vs. CDR-based fraud management – a case study

October 22, 2018

FCC proposal to curb domestic telecom fraud

September 27, 2018

SIP Analytics® inspects each call before it begins. It’s the fastest, most precise method available to detect and prevent telecom toll fraud.

Learn more about SIP Analytics